The 2022 ForRangers Ultra race diary, by Kenneth Donaldson, Save the Rhino Patron and twice ForRangers Ultra runner.

This is an account of our attempt to complete the 2022 “ForRangers Ultra” in Kenya. This blog will contain references to some objects which would not typically appear in a race diary such as:

- An Enormous Avocado

- A Punchbag

- Thieves with bright blue testicles

You will be reassured, perhaps, to know that it will also contain some of the things you might well be expecting such as:

- Blisters (many, multiplying daily)

- A medi-vac airlift

- Freeze-dried food, variously scoffed / untouched / supremely out of date

Introductions

But I am getting ahead of myself. I should start with introductions. Back in 2018, Cathy (my wife, and CEO of Save the Rhino) and I met up with friends Graham and Laura (G&L), and a neighbour of theirs called Charlie, for a few days walking in Italy. Laura and Graham had got to Italy by walking there from their home in Hampshire, and were heading on down to Rome on an epic 1,450 mile “Home to Rome” journey. The rest of us had rather more prosaically flown in to accompany them for a few days. Cathy and I were enthusiastically praising the “ForRangers Ultra”, and to our delight the others took the bait. We all signed up for 2020. While G&L clearly had considerable form as long-distance walkers (masterful understatement!), this would be their, and Charlie’s, first ever formal ultramarathon, doing “marathon plus” distances day after day.

An overview

So, what is an ultramarathon? In this case, 220 km of heat and dust across Africa, spread across five days, averaging a little over a marathon a day. A little… Perhaps I should rethink that description. After you’ve completed a marathon, even 10 extra yards is not “a little”, it’s a painful prospect on aching feet and muscles. Our longest day would be closer to 50 km, which is 8 km more than a standard marathon – an immensity of extra slog on very tired feet.

What else is an ultramarathon? It’s carrying all your kit for the week; food, medicine, bedding, GPS and compass, emergency equipment, toiletries, and if you have room, a spare pair of socks. Perhaps 12 kg, crammed into a rucksack, with whatever you are wanting invariably stuck in the bottom somewhere.

Needless to say, an ultramarathon is more or less as tough as it sounds. Fun runners need not apply.

False start

Five friends, five days, 220 km to go. Ten legs and 10 feet doing diligent training in preparation for our September 2020 adventure. Ah, the best laid plans… I still find it incredible that after not one but two years of postponement, our band of five managed to stay in the game and all actually made it to the start line. Just getting that far deserved a big shiny medal.

We have a friend called Oli. He did the ForRangers Ultra with me and Cathy and some other friends in 2018. He is a great supporter of rhinos and of rangers, the twin pillars of this race. Oli is big-hearted enough to find the time and energy to support other causes too… which is why, a week before we flew to Kenya, I got a message asking if I could ferry out a punchbag to a gym in Nairobi that works to keep kids off the streets and channel their energies positively via boxing.

Sure, I can do that Oli, anything for you. Then an enormous 9 kg misshapen lumpy package wrapped in masses of bin liners and gaffer tape turned up on my doorstep. Nice one Oli. A three-foot long neoprene type of a bag with heavy chain. Leaking slightly. Turns out it’s an aqua bag, you fill it with water before you batter the hell out of it. I am a nervous traveller. I don’t like visas, Covid passes, customs forms, passport controls. All of it worries me needlessly and constantly. In Kenya, plastic bags are banned but I had various ziplocks full of my daily porridge ration, peanuts, cashews and Bertie Bassets (my secret weapon). Now I also had a leaking rubbery punchbag and chains to explain away to the hostile customs official (interrogator) of my imagination. Brilliant. “Oh yes, officer, of course it’s mine, I always travel with my punchbag”. Implausible, given I weigh in at less than 60 kg. Less flyweight more microbeweight.

It was therefore a predictable (but huge) relief when we sailed straight through without a backward glance and on and up to Laikipia to join the rest of the 56 competitors at the campsite on the eve of the race commencing, only four years after first signing on.

Taxi wisdom

We got a taxi to our hotel before heading to Laikipia. I had a chat with the lovely lady who picked us up:

Taxi Driver: “Where are you from?”

Me: “London”

Taxi Driver: “How’s London?”

Me: “Everyone is sad. The Queen is dead”.

Taxi Driver: “No! You should not be sad. She was old and had an excellent life. You should celebrate. You should not be sad. The Queen, we like her, and you should celebrate.”

Back to the Ultramarathon…

If you are reading this, you are probably perfectly well aware that this epic and wonderful, brutal and testing Ultra is all about Rhinos and the Rangers who protect them. What you may not realise is just how complex it is to stage this not-for-profit race at all. It requires a seamless coming together of:

BtU, or Beyond the Ultimate, led by the exceptional Kris King, provide the adventure racing knowledge and experience of what needs to be where and when.

The Medics, one for every six runners, keeping us alive and tending to blisters, dehydration, post-traumatic shock, and everything else the race threw at us. (Several runners needed counselling after witnessing a major and horrific traffic fatality on the way up to the start. Doctor Pete was on hand to help, and as head medic for the RNLI, no one could have been better placed.)

The Rangers, led and coordinated by Sam Taylor, all 150 of them, our eyes and ears, checking for lions, buffalo, elephants, rhinos, hyaena, and anything else that wanted to trample or eat us all up. Without Rangers, no race. More to the point, without them, no wildlife in the first place. The race is largely to provide funding to get these men and women the kit, training, and life insurance that they need to be able to do their difficult and dangerous job safely and well. 100 rangers die on duty on average EVERY YEAR. One died in Laikipia just before we got there, in a fire-fight with cattle poachers. One died in Lake Nakuru National Park just after the race, trampled by a rhino. This is not an exaggeration… this is a hellishly difficult and dangerous – and vital – job. I couldn’t do it. Could you? The supporting umbrella established by Sam and a friend is called ForRangers, and that’s what this race was. ForRangers. For ever.

And for rhinos, the key species they are protecting, the placid prehistoric eye in the centre of a manmade storm of vanity. Because it’s now mostly vanity that drives this insane market. Horn is used as an indicator of wealth, power and connection. Jesus, get a shiny red sports car. Get a Rolex. Or just get lost. But that’s the market driver, as financial folks are wont to say. So Save the Rhino is the fourth organisation playing its part in this ultra-Venn-diagram.

The British Army. They provided the 40 or so tents and dug the latrines and hung the bucket showers (cold, good for you). And moved them each day. And got up at 4 am to get the hot water on for our porridge breakfasts. And kept the camp spic and span. And generally looked after us. And did so cheerfully and wonderfully.

Then there’s the air cover. Fixed-wing plane and chopper. More of that later.

It’s quite a circus, and Kris is quite a ringmaster.

The night before, Camp Zero, we assemble in our serried ranks of two-man tents, assigned to us by the wonderful Kat, a Glaswegian, a pithy problem solver par excellence, who manages to radiate smiles and warmth at the same time. Awesome. (Kat is matched by the wonderful Jenny, whose smile at the finish line each day takes at least 1 km off the route. Aside from smiling, I am told she’s a round-the-world yachtswoman. Pure class.)

We were assigned tent 13; one tent, two army cots, our moveable home for the next five nights. First on the duty order is kit inspection, to check you are actually carrying all the mandatory medical kit, the requisite 2,200 minimum calorie count per day and all the specified survival gear (such as torch, whistle, space blanket, compass, phone). All very sensible, but not much help if you’re trampled by an angry buffalo.

The tent over from us was mid-inspection when there was a call to gather round for a key lecture on avoiding angry buffs and other critters. All the vital rules to keep everyone safe. With kit inspection paused, we listened to the unfolding race etiquette with an increasing sense of foreboding. Thus it was that the ever-watchful monkeys seized their chance. They also seized what looked like a very good amount of the 2,200 daily calories that had been left in the open by our tent-neighbour, who rushed back in time to see his carefully planned treats disappear, held high in triumph over the head and bright blue bollocks of a delighted little simian thief. One-Nil to the wildlife.

Night fell. As did the temperature. Actually, it didn’t so much fall as plummet. In 2018, Cathy and I and absolutely everyone else (race director and experienced African hands alike) suffered horribly from the bitter cold of the nights… no one slept. The 2018 winner, in his acceptance speech, said without irony that the term “endurance event” applied not to the running but to the night-times. I don’t think many people got anywhere near 40 winks, although Cathy and I were mostly ok, having come prepared this time around, albeit with much bigger, heavier packs as a result. Everything comes with a cost in Ultras.

What makes Ultras hard, number 1. SLEEP DEPRIVATION.

They are usually held in inhospitable geographies. Race organisers are fond of deserts, whether ice or sand, and of mountains and fjords. It is invariably really cold at night in these places. If you’re carrying all your kit there’s always a trade-off. Comfort versus lightweight. As a result, most people are increasingly sleep-deprived despite the mounting exhaustion as the race progresses.

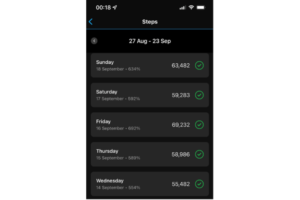

Day 1 37 km 8.75 Hours 55,500 steps Hilly

Finally dawn and the porridge and one of my 10 precious teabags, then the countdown, and finally, finally, two years late, we were off. And as our team were walkers, we didn’t so much burst from the start line, but rather we sortied forth, full of chat and trepidation.

As it happens, we probably had too much of the chat and not enough of the trepidation. About an hour later, we met Kris on a corner into a local village, grinning like a schoolboy. Come see this, he says, as he waved his phone around. Turns out we had all just walked past a large, sleeping, male lion, 50 m off the path.

On we walked. The temperature rose and rose, as did the hills. Gently and then deceptively steeply we climbed and climbed up to over 2100 m above sea-level, from our start-point base at 1700 m. In total we climbed about 750 m this day, which is a decent-sized mountain to chuck into an Ultra. It would get worse, of course.

Today on paper was the “easy” day. A bit shorter, to get people into the swing. However, for Laura and anyone else who gets hit by altitude, this was really tough going. Shortness of breath, and a general feeling of lack of strength caused by the thin air. We were higher than most European ski resorts and it felt it.

After many hot hours, and three checkpoints later we finally knew we were getting close to camp. “Nearly” the well-intentioned rangers said as we passed under their watchful eyes. “Nearly” the medics said, as they sped off in a cloud of dust and diesel fumes, having packed up their last checkpoint for the day. “Nearly”, Sam said, as he came out to check on some unseen (by us) animal lurking in the gathering dusk. I swear we came close to clocking the next person who said “Nearly”. After an hour of “Nearly” on hot feet, it became like nails on blackboard. Never say “Nearly” to an ultrarunner, unless you can actually smell the finish line.

That’s what friends are for – Part 1

That night Batian Craig, a mate and colleague of Cathy’s who lives out here (and is named after the highest peak on Mount Kenya), smuggled a bottle of Johnnie Walker Black Lable to us via Harry Dyer the chopper pilot. A smashing way to end the first day, around a roaring camp fire. One day down, four to go.

What makes Ultras hard, number 2. ALTITUDE SICKNESS

It’s not a feature of every Ultra but we have done a couple at high altitude; this one and one in the Atacama Desert in Chile (that one is properly high up). If you suffer at altitude as Laura does, it’s horrible. All that training, feeling great and then when you have to go uphill all of a sudden you’re at zero miles per hour and feeling weak as a kitten. It means more time in the heat, and mentally it’s a tough place to be. Cathy also struggles at altitude, but Laura had it worst.

Day 2 43 km 9.5 Hours 59,000 steps More Hilly

Longer, and with some real punchy hills, adding to about 1,000 m of climbing during the day. For a lot of first timers, today proved too much. For example the lovely Tabitha, an Aussie girl who was all of 22 years old, had not felt hungry on day 1, had failed to force herself to eat, and consequently had to pull out at checkpoint 1. CP1, like all of the checkpoints, was on top of a hill. Gives them great visibility. But it’s a bit wearying for us poor runners and walkers. This CP was about 10 km of straight climbing out of camp, or at least that’s how it felt. Several others fell by the wayside as the day ground on. Laura’s battle with altitude continued but eventually we made it in, at about 5:30 pm, with an hour or so before darkness and the cold night set in. Just about time to take a cold bucket shower and prep my snacks for tomorrow’s march.

That’s what friends are for – Part 2

By the middle of day 2, Cathy’s shoulders were killing her. We’d borrowed rucksacks from Oli (he of the punchbag) so we could get in some extra layers for the night; our own lightweight rucksacks were just a wee bit too small. And Cathy’s borrowed rucksack had no waistband so all the weight was pressing and bruising her shoulders.

And by the middle of day 2, we arrived at Borana Conservancy’s very new and wonderful education centre. Borana is the second Conservancy we passed though… Lewa, Borana, Ole Naishu, Lolldaiga, Ol Jogi, and Ol Pejeta. All with rhinos save Ole Naishu and Lolldaiga, though the hope is that one day they will have them too. And all supported by Save the Rhino. Cathy had, in March this year, written several successful proposals to grant-making organisations to build an education centre for local communities in Borana… to educate the children on nature, and for use by adults as a meeting space. It had been built out of an old tannery. It was magnificent. With solar power, recycled glass-bottle windows and flooring, a projection room, info on the walls, and a bus to bring in the kids. All in under a year. Cathy is truly awesome. Which is why everyone out here loves her. Batian with the Black Label was only the start. Now it was Michael Dyer’s turn, who is Managing Director on Borana, and who was pleased as punch with his new education facility, as he proudly showed us around.

When Michael heard Cathy was struggling with her rucksack, a plan was made, and sure enough when we finally got into camp, an alternative rucksack from Michael’s son Llewellyn was on offer and it was perfect. Shoulders, and most likely, Cathy’s whole race, was saved.

On the way back from the (very cold) shower, I asked Kat if anyone else was out there, and yes, there was. At about 6:30 the last couple came in. Any longer and the organisers would have had to pull the plug… there’s no way you can safely walk about in the dark. I suspect Kris and Sam only let these guys finish because it was a really open terrain, with no bushes for predators to hide behind in the gathering gloom, plus they had a few rangers to walk with them and keep watch.

As they crossed the line, the whole camp rose to clap them in. Very touching, but we all knew how hard an 11½ hour shift really is; they had earned the applause. As they came home, one looked strong and one pretty wobbly, so I guess it had been a case of nursing his mate over the line.

The pair of late arrivals went to hand their GPS trackers back to Kat for recharging, and then Mr Wobbly basically collapsed, down like a sack of potatoes. Turns out he was from the Danish Military, had failed to eat anything during the day, had not drunk any water either (!!!) and was running on adrenaline. Which you can do, but as soon as you step over the line, your body washes through with relief, the adrenaline flow stops, and that – according to Doctor Pete – is the absolutely most likely time for a heart attack. Which is why they insist on a defib at the finish line. Our man just looked dehydrated and basically buggered, but then came around enough to say he was A) a heavy smoker and B) had chest pains. Cue Harry, the chopper pilot for a medivac flight to the local hospital. In the dark. Cue also a very tense evening for all of us, but most especially Kris, who carries ultimate responsibility for the runners’ safety and who cares very much that we are all properly looked after. As the camp had no phone signal, it was going to be a long wait for news.

Harry’s Story

I said earlier I would return to our air support, and now seems a good time. They are here to get up in the sky at first light, scout for animals, and clear the big beasts off our path. A chopper can, if carefully and sensitively flown, just manage to ease even the elephants away from where they are temporarily not wanted. The only critter they can’t shift is a single male buffalo. He won’t budge for anything or anyone. They don’t push the animals back far, and they don’t hold them for long, as we cannot and would never want to prevent an animal from getting to a source of food or water. Especially water. But it’s a key part of the race, we could not run without this work, even with 150 rangers on the lookout.

Harry used to fly fixed-wing, light aircraft. He’s born and bred locally. He’s a lovely fellow. And in 2017 he died. Or should have. He (by his own admission) banked his plane too hard, and came down. The plane hit the ground and caught fire. Harry was badly burned, and trapped inside. His hands suffered terrible burning as he managed to get clear of the cockpit. He had severe burns over half of his body and he was 6 km at least to any sort of human habitation.

So he set off, 6 km, across the bush, and through a river full of hippos and crocs. (I am not making this up.)

He finally got to some village. Somehow they got him to the local hospital. Which got him to Nairobi hospital, which had no burns unit. And they then got him to South Africa. He really should not have been alive at this point. The SA team did their best, and finally got ready to pass him to the USA. It was said he had a less than 1% chance of surviving that flight. When they got there, he was given some new treatment. But up until then people only got one dose of this stuff, and either lived or died. Harry broke all records and after 8 doses he had an unbelievable number of operations. He battled through the complete failure of his lungs amongst other things.

One of the only reasons the States consented to take him at all, a precondition, was that you have to be pretty damned fit, to have a hope of making it. When they heard Harry was an ultra runner… having done BTU’s Jungle Ultra – that tipped the balance. Benefits of running ultras, one I hope never to test.

So now, looking amazing, calm as you like, Harry is back flying. He’s now switched to choppers. Well, wouldn’t you? Far more fun.

When he got back to Kenya he started fundraising and raised $3.5m to pay for a burns unit for Nairobi hospital.

Respect, although that now-overused word doesn’t even begin to cover it. Doctor Pete was in awe, as Harry is something of a legend in certain medical circles. https://eskenazihealthfoundation.org/harrys-story/

Day 3 49 km 11 Hours 69,200 steps 2 big hills and a cliff

We woke to news that the collapsed Dane was fine, now in a hotel and well on the way to recovery. Meanwhile… Day 3 was the longest day. It was the one to fear. Especially for walkers, out in the sun and the dust for so very long, the dangers of dehydration and exhaustion are high.

And off we trotted. Charlie’s feet were by now falling apart. She’d done all the training, put in the miles, was using familiar kit, had done everything by the book. She’d never suffered from blisters before. So why now? Totally unfair.

Blisters seem to breed blisters. Blisters on her toes, on her soles, and an extraordinary and miserably painful one on her heel. This is not how you want to set off on a 49 km, 11-hour walk.

Charlie is however, made of tough stuff. She was a Karate Black Belt until retiring from that discipline recently. There was never any hesitation. On we went.

In happier news, Laura was acclimatising to the altitude and could walk more freely than days one and two.

What makes Ultras hard, number 3. ATTRITION

It’s seldom a big spectacular injury that takes people out of an Ultra (like snapping an Achilles tendon or breaking a leg) it’s what you might ordinarily think of as “minor” (like a blister or aching shoulders, or chafing) which just gets worse and worse and worse, to the point you can no longer function. Once something starts to go, like hip ache, then you start walking / running differently putting new strain on different joints and it pretty soon all falls apart. It’s a horrid way to exit, a slow death in running terms.

We had been advised in pretty strong terms to take in as much or more water and food at the beginning of the day as possible, as a bank, and then to keep eating and especially drinking. All very well, but Cathy and I had only got 2,200 calories per day, the minimum requirement for the race, because we wanted the extra rucksack space for warmth. Sleep deprivation or calorie deficit. You choose.

I scoffed my plain old porridge and Cathy did her best with her rather fancy (gluten-free) porridge and berry mixture but she really could not face it. There’s something about freeze-dried, packet food that just physically repels her. At least she had eaten more or less a square freeze-dried meal the night before, so day 3 was not starting on complete empty, but it didn’t bode too well. (She has form in not eating freeze-drieds. And being a frugal sort of chap who can’t bear waste, I dug her old rejects from ultras past out the back of our cupboard, determined to use them up this time around. I got Kat to guess the sell by date of my evening meal. Way out. September 2009. It was just fine.)

We trudged on together. There was an extra checkpoint in this long, long stage. They came at roughly 10 km intervals, with the last at 7 to go. At each CP there would be a one or two BtU team members and a couple of medics. Every runner got whoops and hollers and cheering to the skies as they approached. It really does make a difference. You’re so glad to see the checkpoint and tick off another fraction of the day’s race, but the welcome and the applause and whistling just lifts the spirits. 10 or 15 minutes to collect oneself and, in Charlie’s case get her feet retaped, then onwards.

The last checkpoint was “only” 7 km to go, but there was a very considerable sting in the tail. All day long we’d been approaching the mountains that separate Lolldaiga from Ol Jogi. Now we needed to go up and over them. It looked for all the world like a cliff face. And we were pretty low; tied, stiff, footsore (or in Charlie’s case, footagony). We had already done a marathon distance. “Nearly there” said some well-intentioned person who shall remain nameless, Sam. Nearly there my @!*£. It was likely going to take getting on for 2 hours to walk that last 7 km.

Nothing for it, on and up we went.

When we did, finally get up to the ridge, I have to say the view is one that will stay with me for life. The whole race is set in utterly breath-taking scenery. But this was the absolute crown. In one direction (where we had just come) rolling (very large) hills and African plains. And now, looking down over the other side, a forest of Acacia, green and wonderful, with rock kopjes poking out here and there.

We walked along the ridge, taking in the views, to where Kris and a medic had parked up under a huge fever tree. (Well, being Race Director has some perks, best seat in the house.) Kris was standing on the roof with binos pinned to his eyes and he points to… two rhino, placidly eating at about 50 yards away. No way they ought to have been up here. But there they were, a stunning sight in a stunning location. And all too soon we had to turn and continue the last 3 km to our camp and cold shower.

That’s what friends are for – Part 3

On the way to the bucket shower and latrines, Cathy bumped into another friend, Jamie, who is the conservation manager on Ol Jogi. And lo! Cathy’s cold open-air bucket arrangement suddenly morphed into a lovely warm shower in a proper bathroom with actual porcelain. And a tin of lager, which I am happy to report she shared with me.

Cathy was by this point more or less done in. I tried to get her to eat, but by now she was literally gagging whenever she even tried to brush her teeth, such was her loathing of the food she was carrying.

Two marathons, plus a bit, to go. And zero calories. Again, it did not bode well. At least she had been drinking well. And Doctor Pete seemed relaxed. So off to bed to recover and see what the morning brought.

What makes Ultras hard, number 4. CALORIE DEFICIT

The maths is simple. Calories in = 2,200 per day, assuming you eat all your rations. Calories out = 4,000 – 5,500 depending on the day and which watch you’re measuring with. Net result, a very big shortage of calories, for which, read energy. And that’s for five days straight. By the end, most people are running on close to empty, even if they have been fuelling up. If, like Cathy, you can’t bear the thought of eating any more freeze-dried, then you will literally be running on empty. Really not a great strategy for marathon running. Cathy at least managed to keep hydrated, and push down some rehydration powders, which was probably the only thing which kept her going. That, plus sheer force of will.

I have some non-mathematical proof also, in that Graham organised a “Not the Kenya Ultra” when the event first got postponed. Five marathons around Hampshire, camping in friends’ gardens… but crucially we got fed and watered every evening. I won’t say the thing was a picnic, but by the end we were all in pretty good shape. Sure the climate played a part, but largely I put this down to great home cooking and calorie replenishment. The real thing is MUCH harder.

Day 4 43 km 9.25 Hours 59,300 steps A couple of hills

Another freezing night, but Cathy and I slept ok, with our extra fleeces. In the morning, Doctor Pete took another look and gave her the all clear, so we were off, three days down (including the longest stage), and two to go. There was an atmosphere of determination now setting in… surely we had broken the back of this race? However, having previously done this in 2018, this was the day I feared the most. I remembered ferocious heat on the plain, I remembered it being a bloody long way to go, and I remembered thinking it would never end. You were basically still way too far from the finish-line for its gravity to pull you in. The “nearly there” thing that was setting into people’s minds was a major trap.

Day 4 did however have a big highlight; an erosion gully. Spectacular scenery by any standard. But after that, 38 more hot kilometres.

Finally, finally, we made it. It was just as I had remembered. Bloody hard.

That’s what friends are for – Part 4

Harry had heard Cathy was nil by mouth and was all for sticking an IV drip into her. Sam also knew the story, and rather more practically drove over to Jamie’s house and raided his kitchen. He then fetched up at camp with the largest avocado I have ever seen. Plus some apples, some dried fruit, including some beautiful dates. And a tin of baked beans. All of this is of course strictly against the rules. It’s a self-sufficient race. You’re not supposed to get a kind of bush Deliveroo. But Cathy badly needed to get some fuel in her belly, and the avo was just the job. She also managed about a third of the tin of beans. I gratefully hoovered the rest.

Day 5 46 km 9.5 Hours 63,500 steps Flat!

The morning started as ever with a race briefing from Kris. 46 km. Nearly a mutiny. Certainly a lip wobble. Seriously!? On the last day! 4 km over a marathon! Give me a break! We were so desperate to finish and to get a cold beer and some actual foot and to STOP WALKING and it was not going to be a final romp, it was instead going to be a hard, hard day. At least it was flat. But still.

And so, we set off. And we kept on going. And we didn’t hang around at checkpoints. And we finally, finally, got to the last CP of the race. Graham started a countdown. 7 km to go. 6 km to go. 5.5 km to go. On and on. Someone drove past and said “Nearly”. Please stop with that.

And then we actually saw it up ahead. And it was real.

Charlie burst into tears. Anyone else would have pulled out of the race days ago. Her feet were in agony. She had every right to burst into tears. I think we all got a bit emotional. I certainly did.

We crossed the line, five of us in a row. Two rangers walking us in. Magic. Pure magic.

Kris was there to hang medals on us. More tears. But before he could put a gong on Cathy, she pulled him to one side and told him she was DQ-ing herself. Disqualified. Out. Because for the last day and a half, I had carried her pack for her. The rules are you have your pack on you at all times, it’s in part a safety measure. But she’d never have got through those days with an extra 10 kg on her back. Besides we were always in lock-step, so the danger of being separated from your medical kit or GPS was nil. But nonetheless having a porter is not in the rules, so, scrupulous to the end, she DQ’d herself. Kris said something I didn’t catch and gave her a medal anyway. And if you check the results page, he very generously managed to look the other way, as we are all there, listed as finishers. Quite right too.

We came in 38th equal out of 56.

Charlie won the prize for oldest female competitor (and toughest in my reckoning). Also quite possibly the oldest to have completed any of the past ForRangers races.

In fact our team included the three oldest women in the race. As Laura said, not many grandmothers were running races through Africa.

And we all finished. And finished well.

Stunning scenery. Superb organisation. A lovely gold medal. And a cold beer. Total bliss.

2023 anyone?

If you have enjoyed this diary, please do consider sponsoring us. Here is a link https://www.justgiving.com/fundraising/kenneth-donaldson3

On behalf of the rangers and the rhinos, Thank You!